An Unexpected Act of Courage

I got kind of obsessed with the question, “what’s wrong with being right?” after my conversation with Kimeshan and Ryan, that I posted earlier this year. So I asked my friends Lisa & Howard Goldman the same question.

Lisa and Howard work with leaders and teams from some of the biggest companies in the world so they know a thing or two about successful leadership. Here’s (most of) of our talk, which we had on one of their epic walks:

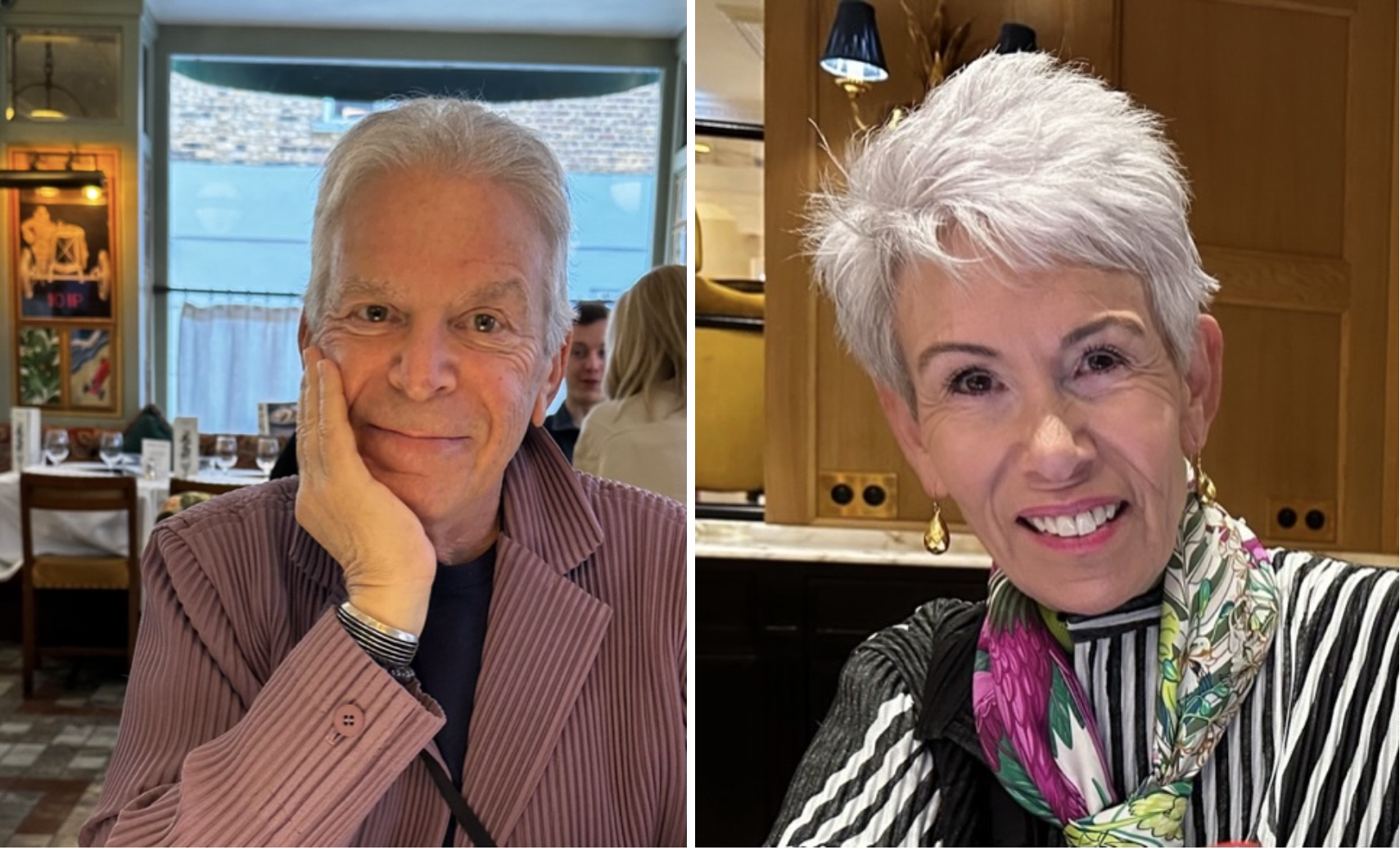

Howard and Lisa Goldman

Patty: Don't be nervous, you two. But I hope you have given this a lot of thought because these are going to be very hard questions.

Lisa: Howard was up half the night.

Patty: I'm so happy you're taking this seriously Howard! So let’s get to the main question. “What's wrong with being right?”

Howard: It should be a Blues song.

Patty: I hope the question spurred memories of working with all the people you both have worked with—leaders, executives, over your careers. In your experience working with those folks, in what ways does “being right” cause mischief?

Howard: I’ll start with my own experience as a management consultant. I learned painfully in the early days of my practice that when I was brought into a company and I offered answers or solutions or points of view that were not inclusive of other people's perspectives, I would be rejected like a foreign body. The more right I was, by inference, I was making others wrong.

Patty: Say more about that. What was the impact on the folks around you when you went in with your rightness and they didn't have an opportunity to contribute?

Howard: Well, they felt disengaged. Being effective and being right are not the same thing.

Lisa: What I would add is the notion of winning. Most people want to be right because it's a win. “Yay. I won!” Everyone capitulates so winning kind of snuggles up to domination—that win, actually equals the crushing of other people, the crushing of their spirits, the crushing of their participation, the crushing of their wanting to involve themselves. It actually pushes away others rather than pulling them together.

So the notion of domination, winning, being right—they all live in the same sphere, so to speak. If you want to be effective in leading people or gaining followership or you just want the intimacy of friendship or family, you have to really be willing to participate. But this doesn’t mean you need to be wrong.

Patty: So the opposite of being right is not being wrong. It’s not a zero sum game. I think people assume, “If I'm not right, then I must be wrong.” How do you coach leaders on this?

Lisa: Being accurate and being right (I'm putting the word “right” in quotes) are not the same. You can be accurate, but how you communicate the accuracy of your view and bring people to see what you see, the conclusion you've come to, is an art. If you try to compel or enforce your accuracy, it reduces people’s connection to you and often makes them feel wrong or stupid or dominated.

Howard: Yeah. You can't use accuracy as a hammer.

Lisa: That's why asking questions is a very powerful way of leading people into a discussion where you can introduce your view, connect to their views and reach conclusions where people feel honored.

Patty: Yes, you both have written about this, particularly in the realm of problem solving. Can you say a little bit about that? Like, how you use powerful questions in problem solving to get the collaboration that you're talking about?

Howard: Yeah, powerful questions are different than questions. My definition of a powerful question is one that starts with how or what and the reason.

Lisa: You learned that from Jeopardy.

Howard: Yeah, and I learned that from you too. The love keeps circling around. The source code for this is when you ask how or what, you're pointing towards the future: “How can we produce this?” “How can we create a product that..?” “What is the most effective strategy to overcome this situation?” These have everyone faced towards the future. Whereas questions that start with why, for instance, have us turn around and look at the past. By the way, “How the hell did we get here?” is a crafty “why” question.

Patty: That is a crafty “why” question!

Howard: Yes and resolving it really augers down the conversation to blame and explain. So let's say “it's engineering's fault!” We all agree so now what? It doesn't matter that it’s engineering's fault. The “now what” is the question to ask to get everyone pointing towards the future and into action. Asking questions is the accelerant to get into action and collaboration. That's the juice.

Patty: It is the magical juice.

Lisa: The shadow side of everything we're talking about is being wrong. When something happens—I burn my hand on a hot stove or whatever, the immediate reflex is something's wrong: “who turned the burner on?” Someone is at fault. I get to be right through my victimization.

Patty: Ahhh. Yes.

Lisa: And it’s not just being right; it’s a kind of self righteousness that breeds separation and polarity. Polarization and inaction.

Patty: That point about the automatic reflex of blaming…

Howard: Is just a way to deflect.

Patty: To take responsibility off ourselves? Is that the reason why that's our first impulse?

Howard: It's such a spurious rock to look under. Who cares? It doesn't matter.

Patty: It's a stupid why question!

Lisa: I think what Howard described is really the DNA for reactivity and being in reaction. I get asked all the time, how do I have my organization be proactive instead of reactive? Well, ain't that the holy grail of the question of running a company? What Howard said about the blame game, the “fixing” scenario is where action occurs but by definition, it’s all reactive to the problem. That’s deflecting and deflecting and deflecting. You can ask a question that starts with ‘how’ or ‘what’ without there necessarily being a problem. “How can we become the number one car rental agency in the United States?” Someone just dreamed that up. “How can we win the Super Bowl?” Someone just dreamed that up. This is where pro-activity comes in. The answer to the question “how can you create a proactive thinking organization?” is to start imbuing people's thinking with how or what questions, not who or why.

Howard: This is jaw droppingly difficult. So simple ain't easy.

Lisa: Going back to your point about problem solving, I don't remember who won the Super Bowl last year, or the World Series, or the women's World Cup. But this is what I can tell you about those teams. It wasn't the team that was necessarily the most talented or motivated. They were the teams that had the ability to solve problems quickly and get into action. And that's what business is about; it's about solving problems.

Patty: On that powerful note, we’re going to close with this. Lisa, my experience of you, is that you are masterful at making other people right, at making situations right. How do you do that? Maybe Howard can answer this with you.

Howard: This may seem intuitive to Lisa, but appreciation and gratitude make other people right and other things right. It's not a statement of facts. It’s literally an interpretation which allows other people to win and to flourish and to be honored for their contribution. It's a willingness to yield to others in order to move forward. And it requires practice; it's a muscle that needs to be developed.

Lisa: You can't fake it. You have to have the experience of that appreciation or gratitude to get that excited about it.

Patty: You both have talked and written a lot about acknowledgement.

Howard: Acknowledgement is making other things and other people right and reducing your importance to the situation.

Patty: Good one Howie. That’s the perfect note to end on.

Lisa: Did we say the right thing?

Patty: You said ALL the right things.